Henning Melber. Book Review:

Christi van der Westhuizen:

Sitting Pretty:

White Afrikaans Women in Postapartheid South Africa (2017).

Scottsville: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, ISBN 978-1-86914376-3, 240 pp

Africa Spectrum, 53(1), 133-136.

South African Apartheid still casts long shadows of the former settlercolonial rule and the specific identities it moulded. Christi van der Westhuizen explores in much depth and detail one of these identities – the image created for Afrikaans-speaking white women.

She engages with 25 respondents aged 30 to 65 in focus group interviews conducted in 2011 and 2012 in the suburbs of Johannesburg and Cape Town, and follows up with in-depth interviews with six of these participants. Much of the account gives voice to these women, who seek to position themselves in a post-Apartheid society with shifting identities.

An analysis of the weekly Sarie women’s magazine “as a purveyor of a contemporary, officially sanctioned discourse creating hegemonic white Afrikaans femininity” (9) is used as an additional source to diagnose the hegemonic role model portrayed for this specific group of South Africans. Those under investigation self-identify as Afrikaans-speaking white heterosexual middle-class women, hitherto hardly explored, especially by a woman socialised in a similar background (though van der Westhuizen herself deviates from the dominant norms in significant ways).

Two ideas key to this group of women meeting their role expectations in post-Apartheid society are ordentlikheid (which can be translated as “decency”) and the contemporary version of volksmoeder (“mother of the nation”) – both key notions of Afrikaner [= Afrikaans-speaking White] nationalism: “these women are required to ‘sit pretty’, that is, physically organise their bodies in accordance with certain prescriptions” (4). Not that this looks any longer like the anachronistic blourokke (blue dresses) of the sectarian churchgoing old Afrikaner [= Afrikaans-speaking White] women.

Many of the new Sarie women appear modern, tanned, sporty, socially apt, and anything but old-fashioned. But the limits of individual emancipation appear where they more or less voluntarily comply with certain stereotypes attributed to their role – not only but also in terms of their womanhood.

Democratic South Africa also tests the purity of “Afrikanerdom”: social interaction with the black majority remains largely restricted “to a service relationship, occurring only when black bodies can be usefully employed by white, middleclass subjects” (40). On the other hand, being “decent” precludes an openly racist attitude, transformed often into a form of paternalism, showing “a preoccupation with a projection of the self as moral, a whiteness eager to distance itself from racism, and also pinning racism on white others/elders to deny its own complicity” (41).

To distance oneself, “racism is acknowledged, but personally disavowed and attributed to others, both white and black” (45). However, as the interviews document, language adjusts, but not the internalised perceptions and the mindset of othering. Words are often more carefully selected, but indirectly confirm that the re-positioning does not mean to abandon the earlier self-attributed moral high grounds of `racial´ superiority (which have perhaps since been translated into forms of different “culture”). In the end, lifestyle and modes of self-positioning do not transform fundamentally: “the centre remains white, with blackness as the necessary coconstructive appendage” (53).

This corresponds with a modified but not abandoned version of hegemonic masculinity, aptly described in its various forms as a “patriarchal overseer” (chapter 4) who protects the family by keeping “femininity white and in heterosexual check” (195). Suburban life in Durbanville and Centurion, white Afrikaans-speaking enclaves in the respective vicinities of Cape Town and Pretoria/Johannesburg, reflects a phenomenon of inward migration and a form of cultural escapism. These locations demonstrate features of an almost closed space, where even the waiters in restaurants are often [exclusively] white. It’s the microcosm of the Sarie world, with middle-class heteronormativity “as the bedrock of the white Afrikaans enclave” (188ff.):

“The restoration of ‘the Afrikaner’ [= Afrikaans-speaking White] happens through myriad transactions, local and global, involving the institutions of matrimony and the family” (190). The spheres range from homes to hair-salons, churches and restaurants to whole suburbs: “Afrikaans media products aid inward migration and serve as extensions of these whitened locales that also exclude gender- and sexually non-conforming individuals” (191).

Reading van der Westhuizen’s revealing analysis, numerous Afrikaans songs (liedjies) rang in my ear. These are still a very popular part of daily culture, finding numerous customers in the still-existing music shops with a wide variety of (also female) singers. Celebrating the greatness of Afrikaans (“Afrikaans is groot”), their lyrics evoke images of the world of Afrikaners [= Afrikaans-speaking Whites]: rugby, rural romanticised farm life, the beauty of nature, the devotion of women to men – and at times the sacrifices of men for women. Live performances in club-like venues (often outside of towns or in school-halls in the rural areas) reinforce the self-imposed isolation cultivating the white Afrikaans identity. An analysis of this entertainment-industry would most likely reinforce the findings presented.

As van der Westhuizen concludes, “white Afrikaans identity work, specifically gender contestation, has intensified on the home front, reentrenching the historical centrality of the family in the production of ‘the Afrikaner’” (203). While due to the force of circumstances their Afrikaner nation-state ambitions had to be abandoned, “the spatial aims have been adapted into a neo-nationalist form, involving a quest for cultural, social and economic autonomy” (204).

White South Africa is a privatised enclave that operationalises class and culture “as vehicles for racist micro-injustices, which make spaces inhospitable to black people, especially black people who challenge white racism” (204). As part of such a strategy to keep the Afrikaans “soul” alive, “volksmoeder –womanhood and its co-constitutive manhood-under-restoration are mobilised to reassert ordentlikheid as an ethnic form of respectability” (205). But there is light at the end of the tunnel, and it is not necessarily the train approaching.

Van der Westhuizen points to the ambiguity of shame as a motivating emotional element, which can lead to different positioning. The first is for her the “unacknowledged shame, when subjects retreat into and cling to normative defensive whiteness,” which “remains blind to black people’s humanity” (210). But the alternative is “shame as enabling a deepening of humanness […] to overturn the colonial denial of humanity to black people.” Such “affective practices, particularly shame, pave ways out of apartheid whiteness, but only if acknowledged” (210). As she concludes, this might turn ordentlikheid “into a truly ethical position aligned with […] values of recognition, rather than reheated dehumanising norms from yesteryear” (211).

Such a concluding observation reinforces what we can witness elsewhere, too: “decency” has many versions and forms. It can be restorative in support of hegemonic, oppressive structures in more or less efficient disguise, claiming the right to protect one’s own cultural identity (in the singular) – equated with the only “legitimate decency” that exists – from onslaught by “others” (be they black, migrants, refugees, sexually different – you name it). Or it can be a truly humanist, all-embracing decency, which realises the need to recognise and benefit from the interaction with “otherness.”

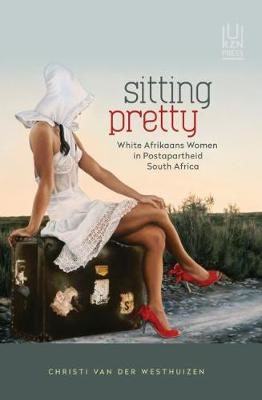

What van der Westhuizen advocates for in terms of South Africa is elsewhere just as relevant, as she writes that “a politics of recognition across the old and the new social frontiers must be pursued. Despite their fresh tweaks, these tired and destructive habits of being and doing may ultimately be our collective undoing. Mutual humanisation through a consciously driven politics of recognition can open new vistas of social imagination” (211). Not by coincidence, the fascinating cover illustration (a wonderful piece of art by Lizelle Kruger) paints a tanned young woman “sitting pretty,” wearing the old hat of the voortrekker-generation but a “sexy” dress, combined with red high heels, while sitting on a suitcase, seemingly waiting either to be picked up – or to stand up and depart.

Henning Melber.

Seems to be an interesting book. Many things of what Henning Melber quotes corroborates with what I experience in the small suburb of Daspoort in Tshwane (aka Pretoria) where I live with my African wife.

As an elderly `mixed´ couple we come across a kind of “friendly” racism (if that is possible at all). White South Africans are rather friendly towards us but at the same time one feels an unspoken/hidden sentiment that “this is not right”.

When we got married in 2012 in Thabazimbi/Limpopo the (white) manager of the social project we were working in said quite frankly that she thinks “this is not right”.

However, to be fair, there are also white compatriots who have no reservations at all. For example some of our (not all) neighbours in the complex we are staying in. Thus a normal neighbourly relationship across the so called colour-bar is possible. That should inject some hope, I suppose…

Sizwe.